A drone photographer is asking the U.S. Supreme Court to protect his aerial images with First Amendment Rights — in the same way as free speech.

On September 9, drone photographer and entrepreneur Michael Jones, who is based in Goldsboro, North Carolina, filed a petition of certiorari with the Supreme Court.

In his petition, the drone photographer is asking the Supreme Court to offer First Amendment protection for his aerial images.

Jones argues that the useful “data” and “information” that he provides clients in his aerial photographs qualify as free speech in the digital age and that state licensing boards do not have the authority to censor it.

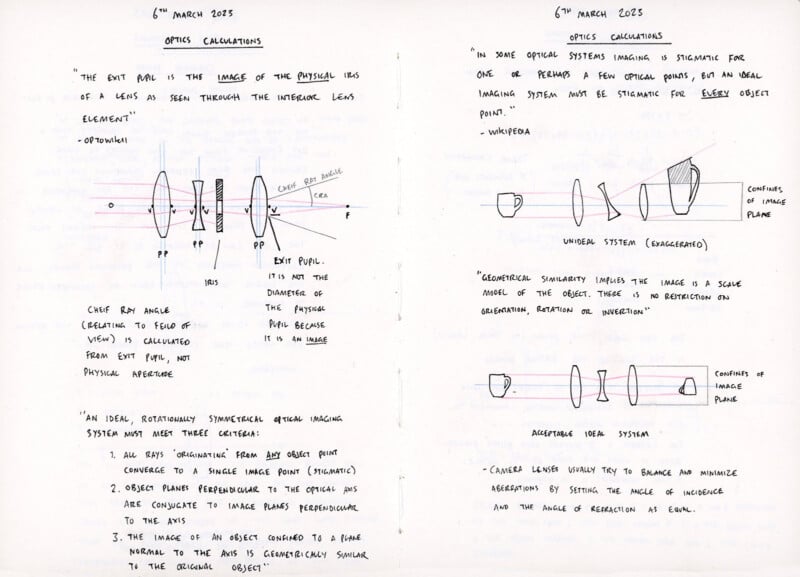

Photographer and FAA-licensed drone operator Jones runs an aerial-mapping business in North Carolina, according to a press release by the Institute of Justice (IJ), the public interest law firm that is representing him.

Many landowners find a bird’s-eye perspective on their property useful in situations where they do not need a full-blown land survey and Jones’ aerial-mapping business provides a solution for this.

Jones takes aerial photographs of private property in North Carolina with the owners’ permission. He then uses publicly available digital tools to stitch the images together into high-definition maps for clients.

Fate of a Drone Photographer Lies With Supreme Court

Jones follows all safety and privacy laws with his drone photography. However, despite this, North Carolina’s surveying board has tried to crack down on Jones’ aerial business.

In 2019, the North Carolina surveying board issued a cease-and-desist letter. The board ordered Michael to shut down his operations or face civil and criminal penalties.

In response, Michael sued the board, arguing that his aerial photographs and maps are forms of speech protected by the First Amendment. The photographer says that government cannot criminalize the communication of aerial photographs simply because of the “data” and “information” they contain.

Now, it is likely that state regulators will shut the drone photographer’s business down — unless the Supreme Court intervenes in his case.

In his petition filed this month, Jones is asking the Supreme Court to take up his case and protect the First Amendment rights for everyone who is simply providing information to willing customers.

“Drone technology may be new, but the principles at stake in Michael’s case are as old as the nation itself,” IJ Senior Attorney Sam Gedge.

“Taking photos and providing information to willing clients is speech, and it’s fully protected by the First Amendment.”

Prior to his petition with the Supreme Court, Jones’ case was rejected by the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in May this year. The court carved out the photographer’s creation of maps as “conduct,” not speech.

“When a government agency sends a cease-and-desist letter telling you to stop communicating photographs containing specific types of ‘data’ and ‘information,’ that’s a red flag that serious First Amendment interests are in play,” IJ Attorney James Knight argues.

“The Fourth Circuit’s ruling was badly flawed, and it spotlights the lower courts’ confusion about the power of licensing boards to censor speech.”

Image credits: All photos via the Institute of Justice